Table of Contents

Go is getting more and more popular as the go-to language to build web applications.

This is in no small part due to its speed and application performance, as well as its portability. There are many resources on the internet to teach you how to build end to end web applications in Go, but for the most part they are either scattered in the form of isolated blog posts, or get into too much detail in the form of books.

With this tutorial, I hope to find the middle ground and provide a single resource which describes how to make a full stack web application in Go, along with sufficient test cases.

The only prerequisite for this tutorial is a beginner level understanding of the Go programming language.

”Full Stack” ?

We are going to build a community encyclopedia of birds. This website will :

- Display the different entries submitted by the community, with the name and details of the bird they found.

- Allow anyone to post a new entry about a bird that they saw.

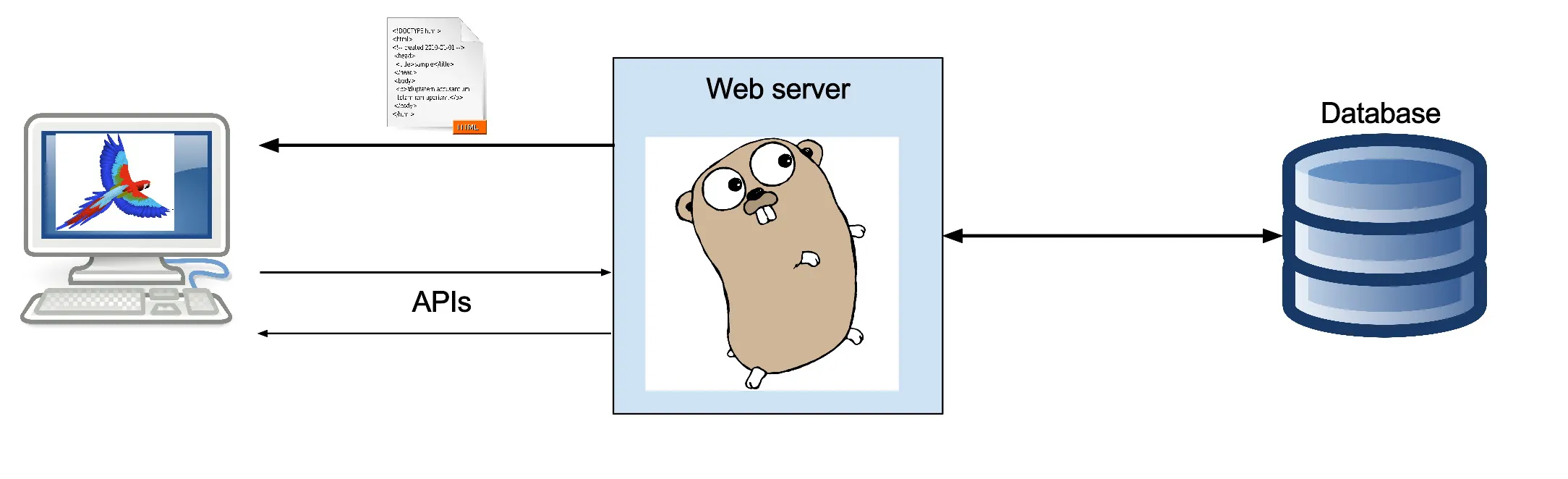

This application will require three components :

- The web server

- The front-end (client side) app

- The database

Creating your project directory

The first thing you’ll want to do is create a new directory for your project. For this example, we’ll call it birdpedia :

mkdir birdpediaAll the files and commands executed henceforth will be within this directory.

Let’s initialize a new module for our project. This will help us install and maintain dependencies that we’ll need to run our application:

go mod init github.com/sohamkamani/birdpediaHere, I’m initializing a new module with the repository I intend the module to reside in. You should change the module name based on your repository location

This should create the go.mod and go.sum files within your folder.

Starting an HTTP server

Inside your project directory, create a file called main.go inside your project directory :

touch main.goThis file will contain the code to start your server :

// This is the name of our package

// Everything with this package name can see everything

// else inside the same package, regardless of the file they are in

package main

// These are the libraries we are going to use

// Both "fmt" and "net" are part of the Go standard library

import (

// "fmt" has methods for formatted I/O operations (like printing to the console)

"fmt"

// The "net/http" library has methods to implement HTTP clients and servers

"net/http"

)

func main() {

// The "HandleFunc" method accepts a path and a function as arguments

// (Yes, we can pass functions as arguments, and even treat them like variables in Go)

// However, the handler function has to have the appropriate signature (as described by the "handler" function below)

http.HandleFunc("/", handler)

// After defining our server, we finally "listen and serve" on port 8080

// The second argument is the handler, which we will come to later on, but for now it is left as nil,

// and the handler defined above (in "HandleFunc") is used

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

// "handler" is our handler function. It has to follow the function signature of a ResponseWriter and Request type

// as the arguments.

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// For this case, we will always pipe "Hello World" into the response writer

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello World!")

}

fmt.Fprintf, unlike the other “printf” statements you may know, takes a “writer” as its first argument. The second argument is the data that is piped into this writer. The output therefore appears according to where the writer moves it. In our case the ResponseWriterwwrites the output as the response to the users request.

You can now run this file :

go run main.goAnd navigate to http://localhost:8080 in your browser, or by running the command :

curl localhost:8080And see the output: “Hello World!”

You have now successfully started an HTTP server in Go.

Making routes

Our server is now running, but, you might notice that we get the same “Hello World!” response regardless of the route we hit, or the HTTP method that we use. To see this yourself, run the following curl commands, and observe the response that the server gives you :

curl localhost:8080/some-other-route

curl -X POST localhost:8080

curl -X PUT localhost:8080/samethingAll three commands still give you “Hello World!”

We would like to give our server a little more intelligence than this, so that we can handle a variety of paths and methods. This is where routing comes into play.

Although you can achieve this with Go’s net/http standard library, there are other libraries out there that provide a more idiomatic and declarative way to handle http routing.

Installing external libraries

We will be installing a few external libraries through this tutorial, where the standard libraries don’t provide the features that we want.

When we install libraries, we need a way to ensure that other people who work on our code also have the same version of the library that we do.

In order to do this, we can make use of the go get command, which helps us install the library of our choice, and adds its version information to the go.mod and go.sum files.

Let’s install our routing library:

go get github.com/gorilla/muxThis will add the gorilla/mux library to your project.

Now, we can modify our code to make use of the functionality that this library provides :

package main

import (

// Import the gorilla/mux library we just installed

"fmt"

"net/http"

"github.com/gorilla/mux"

)

func main() {

// Declare a new router

r := mux.NewRouter()

// This is where the router is useful, it allows us to declare methods that

// this path will be valid for

r.HandleFunc("/hello", handler).Methods("GET")

// We can then pass our router (after declaring all our routes) to this method

// (where previously, we were leaving the second argument as nil)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", r)

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello World!")

}Testing

Testing is an essential part of making any application “production quality”. It ensures that our application works the way that we expect it to.

Lets start by testing our handler. Create a file called main_test.go:

//main_test.go

package main

import (

"net/http"

"net/http/httptest"

"testing"

)

func TestHandler(t *testing.T) {

//Here, we form a new HTTP request. This is the request that's going to be

// passed to our handler.

// The first argument is the method, the second argument is the route (which

//we leave blank for now, and will get back to soon), and the third is the

//request body, which we don't have in this case.

req, err := http.NewRequest("GET", "", nil)

// In case there is an error in forming the request, we fail and stop the test

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

// We use Go's httptest library to create an http recorder. This recorder

// will act as the target of our http request

// (you can think of it as a mini-browser, which will accept the result of

// the http request that we make)

recorder := httptest.NewRecorder()

// Create an HTTP handler from our handler function. "handler" is the handler

// function defined in our main.go file that we want to test

hf := http.HandlerFunc(handler)

// Serve the HTTP request to our recorder. This is the line that actually

// executes our the handler that we want to test

hf.ServeHTTP(recorder, req)

// Check the status code is what we expect.

if status := recorder.Code; status != http.StatusOK {

t.Errorf("handler returned wrong status code: got %v want %v",

status, http.StatusOK)

}

// Check the response body is what we expect.

expected := `Hello World!`

actual := recorder.Body.String()

if actual != expected {

t.Errorf("handler returned unexpected body: got %v want %v", actual, expected)

}

}Go uses a convention to ascertains a test file when it has the pattern

*_test.go

To run this test, just run :

go test ./...from your project root directory. You should see a mild message telling you that everything ran ok.

Making our routing testable

If you notice in our previous snippet, we left the “route” blank while creating our mock request using http.newRequest. How does this test still pass if the handler is defined only for “GET /handler” route?

Well, turns out that this test was only testing our handler and not the routing to our handler. In simpler terms, this means that the above test ensures that the request coming in will get served correctly provided that it’s delivered to the correct handler.

In this section, we will test this routing, so that we can be sure that each handler is mapped to the correct HTTP route.

Before we go on to test our routing, it’s necessary to make sure that our code can be tested for this. Modify the main.go file to look like this:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

"github.com/gorilla/mux"

)

// The new router function creates the router and

// returns it to us. We can now use this function

// to instantiate and test the router outside of the main function

func newRouter() *mux.Router {

r := mux.NewRouter()

r.HandleFunc("/hello", handler).Methods("GET")

return r

}

func main() {

// The router is now formed by calling the `newRouter` constructor function

// that we defined above. The rest of the code stays the same

r := newRouter()

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", r)

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello World!")

}Once we’ve separated our route constructor function, let’s test our routing:

func TestRouter(t *testing.T) {

// Instantiate the router using the constructor function that

// we defined previously

r := newRouter()

// Create a new server using the "httptest" libraries `NewServer` method

// Documentation : https://golang.org/pkg/net/http/httptest/#NewServer

mockServer := httptest.NewServer(r)

// The mock server we created runs a server and exposes its location in the

// URL attribute

// We make a GET request to the "hello" route we defined in the router

resp, err := http.Get(mockServer.URL + "/hello")

// Handle any unexpected error

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

// We want our status to be 200 (ok)

if resp.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

t.Errorf("Status should be ok, got %d", resp.StatusCode)

}

// In the next few lines, the response body is read, and converted to a string

defer resp.Body.Close()

// read the body into a bunch of bytes (b)

b, err := ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

// convert the bytes to a string

respString := string(b)

expected := "Hello World!"

// We want our response to match the one defined in our handler.

// If it does happen to be "Hello world!", then it confirms, that the

// route is correct

if respString != expected {

t.Errorf("Response should be %s, got %s", expected, respString)

}

}Now we know that every time we hit the GET /hello route, we get a response of hello world. If we hit any other route, it should respond with a 404. In fact, let’s write a test for precisely this requirement :

func TestRouterForNonExistentRoute(t *testing.T) {

r := newRouter()

mockServer := httptest.NewServer(r)

// Most of the code is similar. The only difference is that now we make a

//request to a route we know we didn't define, like the `POST /hello` route.

resp, err := http.Post(mockServer.URL+"/hello", "", nil)

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

// We want our status to be 405 (method not allowed)

if resp.StatusCode != http.StatusMethodNotAllowed {

t.Errorf("Status should be 405, got %d", resp.StatusCode)

}

// The code to test the body is also mostly the same, except this time, we

// expect an empty body

defer resp.Body.Close()

b, err := ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

respString := string(b)

expected := ""

if respString != expected {

t.Errorf("Response should be %s, got %s", expected, respString)

}

}Now that we’ve learned how to create a simple http server, we can serve static files from it for our users to interact with.

Serving static files

“Static files” are the HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images, and the other static asset files that are needed to form a website.

There are 3 steps we need to take in order to make our server serve these static assets.

- Create static assets

- Modify our router to serve static assets

- Add tests to verify that our new server can serve static files

Create static assets

To create static assets, create a directory in your project root directory, and name it assets :

mkdir assetsNext, create an HTML file inside this directory. This is the file we are going to serve, along with any other file that goes inside the assets directory :

touch assets/index.htmlModify the router

Interestingly enough, the entire file server can be enabled in just adding 3 lines of code in the router. The new router constructor will look like this :

func newRouter() *mux.Router {

r := mux.NewRouter()

r.HandleFunc("/hello", handler).Methods("GET")

// Declare the static file directory and point it to the

// directory we just made

staticFileDirectory := http.Dir("./assets/")

// Declare the handler, that routes requests to their respective filename.

// The fileserver is wrapped in the `stripPrefix` method, because we want to

// remove the "/assets/" prefix when looking for files.

// For example, if we type "/assets/index.html" in our browser, the file server

// will look for only "index.html" inside the directory declared above.

// If we did not strip the prefix, the file server would look for

// "./assets/assets/index.html", and yield an error

staticFileHandler := http.StripPrefix("/assets/", http.FileServer(staticFileDirectory))

// The "PathPrefix" method acts as a matcher, and matches all routes starting

// with "/assets/", instead of the absolute route itself

r.PathPrefix("/assets/").Handler(staticFileHandler).Methods("GET")

return r

}Testing the static file server

You cannot truly say that you have completed a feature until you have tests for it. We can test the static file server by adding another test function to main_test.go :

func TestStaticFileServer(t *testing.T) {

r := newRouter()

mockServer := httptest.NewServer(r)

// We want to hit the `GET /assets/` route to get the index.html file response

resp, err := http.Get(mockServer.URL + "/assets/")

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

// We want our status to be 200 (ok)

if resp.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

t.Errorf("Status should be 200, got %d", resp.StatusCode)

}

// It isn't wise to test the entire content of the HTML file.

// Instead, we test that the content-type header is "text/html; charset=utf-8"

// so that we know that an html file has been served

contentType := resp.Header.Get("Content-Type")

expectedContentType := "text/html; charset=utf-8"

if expectedContentType != contentType {

t.Errorf("Wrong content type, expected %s, got %s", expectedContentType, contentType)

}

}To actually test your work, run the server :

go run main.goAnd navigate to http://localhost:8080/assets/ in your browser.

Making a simple browser app

Since we need to create our bird encyclopedia, lets create a simple HTML document that displays the list of birds, and fetches the list from an API on page load, and also provides a form to update the list of birds :

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>The bird encyclopedia</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>The bird encyclopedia</h1>

<!--

This section of the document specifies the table that will

be used to display the list of birds and their description

-->

<table>

<tr>

<th>Species</th>

<th>Description</th>

</tr>

<td>Pigeon</td>

<td>Common in cities</td>

</tr>

</table>

<br/>

<!--

This section contains the form, that will be used to hit the

`POST /bird` API that we will build in the next section

-->

<form action="/bird" method="post">

Species:

<input type="text" name="species">

<br/> Description:

<input type="text" name="description">

<br/>

<input type="submit" value="Submit">

</form>

<!--

Finally, the last section is the script that will

run on each page load to fetch the list of birds

and add them to our existing table

-->

<script>

birdTable = document.querySelector("table")

/*

Use the browsers `fetch` API to make a GET call to /bird

We expect the response to be a JSON list of birds, of the

form :

[

{"species":"...","description":"..."},

{"species":"...","description":"..."}

]

*/

fetch("/bird")

.then(response => response.json())

.then(birdList => {

//Once we fetch the list, we iterate over it

birdList.forEach(bird => {

// Create the table row

row = document.createElement("tr")

// Create the table data elements for the species and

// description columns

species = document.createElement("td")

species.innerHTML = bird.species

description = document.createElement("td")

description.innerHTML = bird.description

// Add the data elements to the row

row.appendChild(species)

row.appendChild(description)

// Finally, add the row element to the table itself

birdTable.appendChild(row)

})

})

</script>

</body>Adding the bird REST API handlers

As we can see, we will need to implement two APIs in order for this application to work:

GET /bird- that will fetch the list of all birds currently in the systemPOST /bird- that will add an entry to our existing list of birds

For this, we will write the corresponding handlers.

Create a new file called bird_handlers.go, adjacent to the main.go file.

First, we will add the definition of the Bird struct and initialize a common bird variable:

type Bird struct {

Species string `json:"species"`

Description string `json:"description"`

}

var birds []BirdNext, define the handler to get all birds :

func getBirdHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

//Convert the "birds" variable to json

birdListBytes, err := json.Marshal(birds)

// If there is an error, print it to the console, and return a server

// error response to the user

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(fmt.Errorf("Error: %v", err))

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

// If all goes well, write the JSON list of birds to the response

w.Write(birdListBytes)

}Next, the handler to create a new entry of birds :

func createBirdHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Create a new instance of Bird

bird := Bird{}

// We send all our data as HTML form data

// the `ParseForm` method of the request, parses the

// form values

err := r.ParseForm()

// In case of any error, we respond with an error to the user

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(fmt.Errorf("Error: %v", err))

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

// Get the information about the bird from the form info

bird.Species = r.Form.Get("species")

bird.Description = r.Form.Get("description")

// Append our existing list of birds with a new entry

birds = append(birds, bird)

//Finally, we redirect the user to the original HTMl page

// (located at `/assets/`), using the http libraries `Redirect` method

http.Redirect(w, r, "/assets/", http.StatusFound)

}The last step, is to add these handler to our router, in order to enable them to be used by our application :

// These lines are added inside the newRouter() function before returning r

r.HandleFunc("/bird", getBirdHandler).Methods("GET")

r.HandleFunc("/bird", createBirdHandler).Methods("POST")

return rThe tests for both these handlers and the routing involved are similar to the previous tests we wrote for the GET /hello handler and static file server, and are left as an exercise for the reader.

If you’re lazy, you can still see the tests in the source code

Adding a database

So far, we have added persistence to our application, with the information about different birds getting stored and retrieved.

However, this persistence is short lived, since it is in memory. This means that anytime you restart your application, all the data gets erased. In order to add true persistence, we will need to add a database to our stack.

Until now, our code was easy to reason about and test, since it was a standalone application. Adding a database will add another layer of communication.

You can read about how to integrate a postgres database into your Go application in my next post

**_You can find the source code for this post here___